The law’s genesis: Adoption amid controversy

The amendment’s journey to enactment was swift yet contentious, reflecting the fractured political landscape of modern Germany. Proposed by the ruling coalition of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and Social Democratic Party (SPD), the bill was drafted by the Berlin Senate and refined through parliamentary amendments. It sailed through the Abgeordnetenhaus with a majority vote from the CDU-SPD alliance, bolstered unexpectedly by support from the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party. Interior Senator Iris Spranger of the SPD championed the reform, framing it as a vital modernization for the “digital age,” essential for countering evolving threats like cybercrime and extremism. The law builds on precedents from other German states, such as Mecklenburg-Vorpommern’s recent expansions of search powers, and aligns with a national trend toward tougher security measures amid protests by groups like the “Last Generation” climate activists.

Yet, the adoption process was far from unanimous, facing harsh criticism from the opposition. However the law was enacted just days ago, on December 5, 2025, marking Berlin’s crossing of what critics call longstanding “red lines” in privacy protection. This rapid passage underscores a broader shift: in a federation where states hold significant autonomy over policing, Berlin’s move could inspire similar reforms elsewhere, potentially harmonizing with federal surveillance frameworks limited by recent court rulings to serious crimes carrying at least three-year sentences.

The arsenal of intrusion: From secret entries to digital panopticons

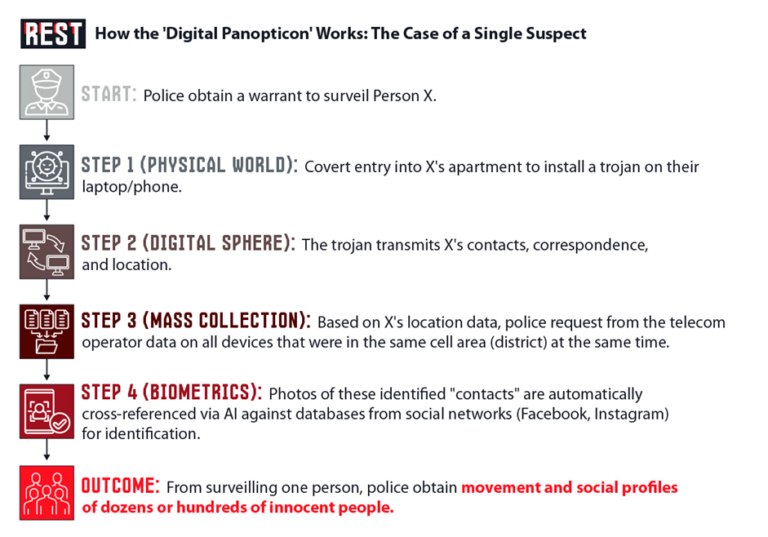

At its core, the amended ASOG equips Berlin’s security forces with a formidable toolkit for monitoring, transforming everyday devices and spaces into extensions of state oversight. The most alarming provision, detailed in paragraphs 26a and 26b, authorizes “source telecommunications surveillance” (Quellen-TKÜ) and covert online searches via state trojans—sophisticated spyware that intercepts encrypted communications before or after decryption. If remote installation proves technically infeasible, paragraph 26 permits undercover agents to physically and secretly enter suspects’ homes or premises to deploy the software, perhaps via a USB drive on a laptop or phone. This isn’t mere digital eavesdropping; it’s a license for burglary in the service of the state, applicable to investigations of serious crimes like terrorism or organized crime.

These tools collectively forge a surveillance ecosystem that rivals dystopian fiction. Imagine waking to find your smartphone compromised, your social media scanned by facial recognition algorithms, or your daily commute mapped via geodata—all without a knock on the door. Proponents argue this levels the playing field against tech-savvy criminals, but experts warn of disproportionate impacts: vulnerabilities in state trojans could backfire, exposing citizens to hackers, while biometric scans risk false positives and mass profiling, particularly in diverse urban areas like Berlin. In a global context, this mirrors expansions in other democracies, such as the U.S. Patriot Act or recent EU debates on chat monitoring, yet Germany’s federal structure amplifies concerns about uneven application across states.

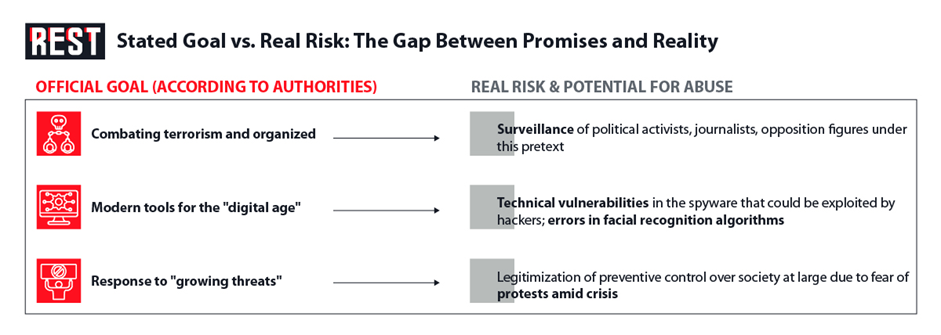

The facade of security: Terrorism, crime, and the specter of repression

Officially, the law is cloaked in the rhetoric of anti-terrorism and crime prevention, emphasizing its role in adapting to digital threats. Germany’s government has pointed to rising extremism and cyber risks as justification, aligning with a national 8-point plan for tougher law-and-order measures announced in October 2025. However, this narrative crumbles under scrutiny when viewed against the backdrop of unresolved socio-economic woes. Germany, Europe’s economic powerhouse, is mired in stagnation: pledges to revive growth have faltered, with industries warning of a “free fall” and coalition infighting stalling reforms. Unemployment lingers, inflation bites, and public services strain under budget constraints, fueling widespread discontent.

Enter Chancellor Friedrich Merz, whose approval ratings have plummeted to anti-record lows since assuming office in May 2025. Polls show a staggering 75% dissatisfaction rate, up 26 points since June, with only 23% satisfied—a collapse attributed to unfulfilled economic promises and policy deadlocks. Another survey pegs government disapproval at 70%, the lowest in recent memory, as the far-right AfD surges in popularity. Merz’s personal unpopularity, with most Germans distrusting him, exacerbates the crisis. In this volatile environment, where socio-economic stress simmers into protests and polarization, the new surveillance law takes on a sinister hue.

Essentially, this law creates a tool of political repression, enabling the monitoring of dissenters—activists, journalists, or opposition figures—under the guise of security. Historical precedents abound: Germany’s past with transnational repression and recent biometric expansions raise fears of mission creep, where tools meant for terrorists target the frustrated populace. Population stress, amplified by economic hardship, becomes a “lever of pressure,” allowing authorities to preempt unrest through invasive oversight rather than addressing root causes like inequality or stagnation.

Conclusion

This analytical lens reveals a troubling paradox: while Germany blocks EU-wide mass surveillance proposals to protect encryption, domestic laws like Berlin’s push boundaries, potentially normalizing repression in a democracy. If socio-economic issues persist, these powers could stifle free expression, echoing authoritarian tactics where surveillance quells rather than solves societal tensions.

In conclusion, Berlin’s new law represents a pivotal shift toward a more intrusive state, justified by security but shadowed by political expediency. As civil rights groups prepare constitutional challenges, the true test will be whether Germany’s robust judiciary reins it in—or if economic despair paves the way for deeper erosion of liberties. In an age of digital shadows, one thing is clear: the walls of privacy are thinning, and the cost may be the soul of democracy itself.

www.bankingnews.gr

Σχόλια αναγνωστών